How to invent Bitcoin

The Bitcoin paper was published in 2008 by a mysterious figure Satoshi Nakamoto. Satoshi’s identity remains unknown and is the source of endless speculation, most of which, frankly, is not that interesting and certainly not the topic of this text.

It’s reasonable to assume that some time before 2008 (perhaps in 2005 or 2006?) Satoshi had a moment, in which he realized that this thing is actually possible or this may in fact work. Specifically, it was an idea on how to resolve a specific problem that arises when you attempt to model the behavior of physical gold in the digital world. Even though physical gold doesn’t deal with history in any way, the key problem that arises is around getting a bunch of unrelated parties to agree on what’s considered to be valid history.

In this blog post, I’ll attempt to recreate the process of discovering Bitcoin and pinpoint that moment that Satoshi had.

Note: this blog post doesn’t endorse or suggest buying Bitcoin. On the contrary, I vaguely believe most of the original intent behind Bitcoin was lost over time and am fairly tired of various bankers proclaiming that Bitcoin is some kind of permanent reserve of value. See the footnote on reasons why I’m writing this blog post 1. I do believe that other solutions in the space now carry the torch of the original idea.

0. Physical gold: the spec

Consider the problem of modeling physical gold in code, see the Bit Gold text from 2005 by Nick Szabo. We’d like to have information that behaves like gold and exist only in the digital realm. Note that this appears impossible at a glance; physical gold is a tough nut to model. It’s not at all like a “typical” programming project, such as creating a ticketing system for tasks that employees ought to finish at some company, or a weather application that picks up data from a measuring station.

Modeling physical gold is thorny because of the following properties:

- (G1) You can exchange gold without any help or supervision from a third party

- (G2) You cannot be prevented from exchanging gold; it is not censorable

- (G3) You ought to be able to mine gold, a third party cannot prevent you from doing so

Note that there are also some properties of physical gold that Bitcoin does not replicate:

- (Z1) Gold has no serial number like cash does

- (Z2) There shouldn’t be any trace of a gold exchange that took place

To model the latter two properties, it’s necessary to use further mathematical weaponry which wasn’t necessarily available in the early Bitcoin times - so we’ll put these properties aside when it comes to this text.

1. Why not just send some hash preimages over email

Let’s start with a simplest thing possible. Satisfy (G3) by having digital gold be represented as a solution to a hard-to-solve equation. The idea is to mimic the process of physical gold mining using a mathematical equation. The equation is public, there are no shortcuts; it’s not hard to find such a puzzle, take for example inverting a hash function. This is called Proof of Work and is a widely known concept nowdays. See the footnote2 for comparison between traditional or “all or nothing” cryptography and Proof of Work.

What do you do with solutions of that equation that represent digital gold? Send them over email or chat apps to exchange them for goods? That wouldn’t work, as such digital gold could be arbitrarily copied and re-spent once it’s received. There’s no notion of who owns what; and thus we arrive to the notion of a non-tamperable notebook of who owns what: a ledger.

2. How to make a ledger trustless

The digital ledger records who owns what, by way of recording all transfers that ever took place in the past; it’s an ever growing database. The ledger must not be stored and maintained by a single entity, as that entity could simply delete the ledger, ending the story right there (and violating G1, G2 and G3).

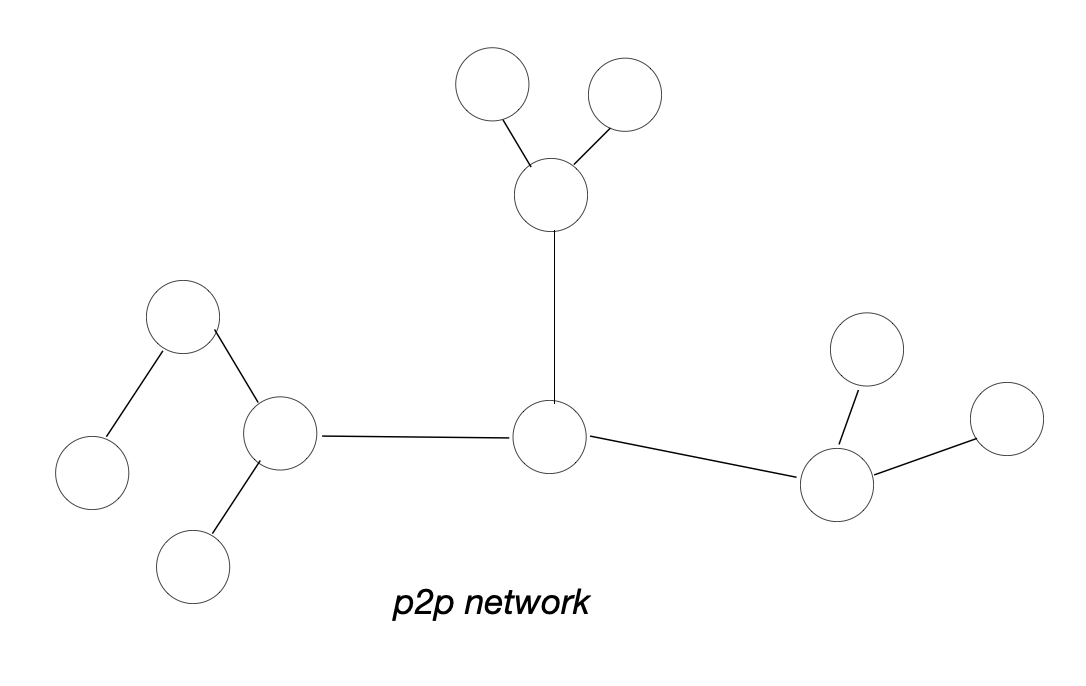

In other words, the ledger ought to be replicated among peers who join the network at will. A P2P network is the right thing here; have each participant store the ledger and broadcast transactions to neighbouring nodes as they arrive. The nodes update the ledger accordingly if transaction validation checks out.

Participants ougthn’t be able to appropriate other users’ funds; a way to authorize transfers is needed. As there’s no central authority or server here, a cryptographic signature is the correct primitive to use. With cryptographic signatures, participants hold secret keys, while the public can validate each signed transfer with a corresponding public key.

Transactions are then signed messages that refer to existing entries on the ledger (so called unspent outputs or UTXO in Bitcoin), spending the totality of a previous ledger entry and potentially sending it off to multiple new public keys. Transactions are broadcast on the network and in order to be in sync with the changes on the network, on each transaction, participants update their view of the ledger.

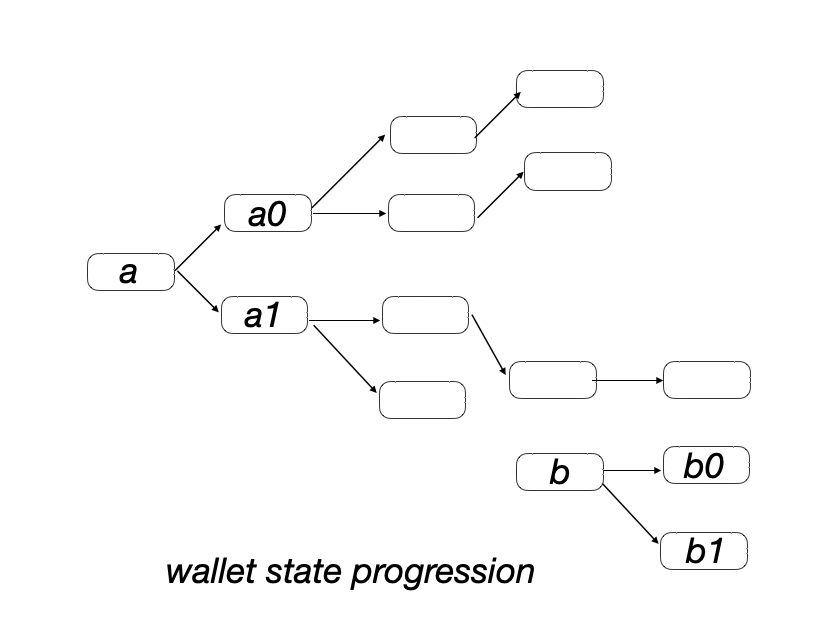

We can now visualize what we envisioned: the P2P network (on the left) and the state of the ledger (on the right). Nodes on the right-hand picture represent addresses (signature public keys) and edges represent transfers. This visualization does not capture entity ownership; in practice, many public keys can be held by a single entity. In fact, we can imagine that public keys are never reused, which is completely fine.

3. How to mine gold

Note that in the wallet picture above, there’s more than one root from which new digital gold emerges; these are instances where new digital gold was mined. Specifically, to simulate physical gold mining (G3), we introduce a special kind of transaction which doesn’t reference a previous unspent output. Rather, it validates the counter solution for a hash puzzle such as:

hash(receiving-address | counter)

The counter value is such that there is n leading zeros in the output of the hash function, which is a problem that takes around 2^n attempts. We added the receiving-address field into the hash in order to mitigate reusing solutions across transactions; this is a security-relevant detail, we’ll just leave it there, even though we don’t try to be very precise in this text.

This looks like a promising direction; there’s nothing necessarily problematic that we’re encountering yet. The mining process could be modulated in sponge-like manner; its difficulty can increase and decrease based on some function. Some transactions mine new gold, some send it off elsewhere.

4. How to create history

There’s a problem, however: nodes are in the dark on what exactly other nodes see as their ledger. A node really has no way of knowing what other nodes see as their valid set of transactions. If a node goes offline, it doesn’t know where to catch up from, what to ask for or what tranasctions should they include in their ledger.

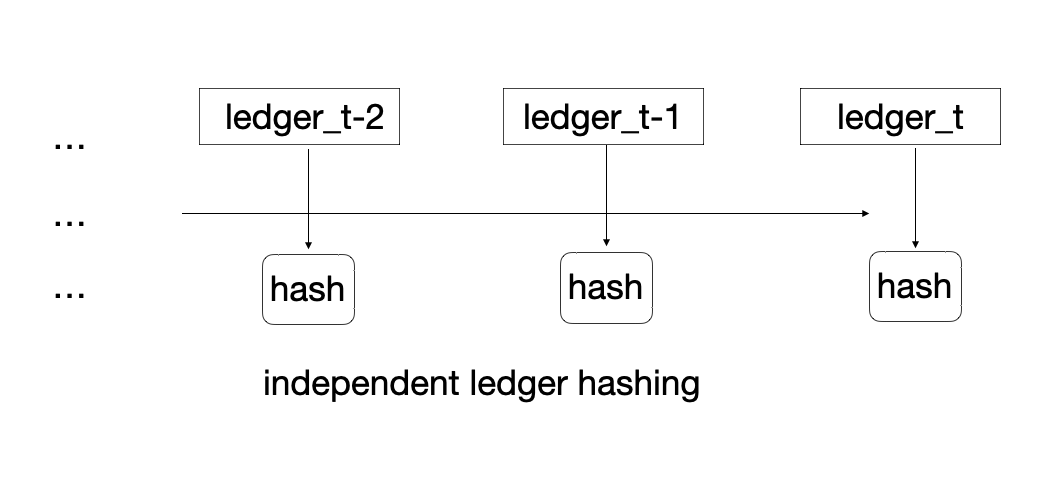

A hash function which is a mathematical emulation of a real-world fingerprint, such as SHA2 can be used to summarize the state of the ledger. In the left-hand side of the picture, a hash of the whole ledger is computed after each transaction. A hash sequence thus uniquely represents the ledger’s evolution:

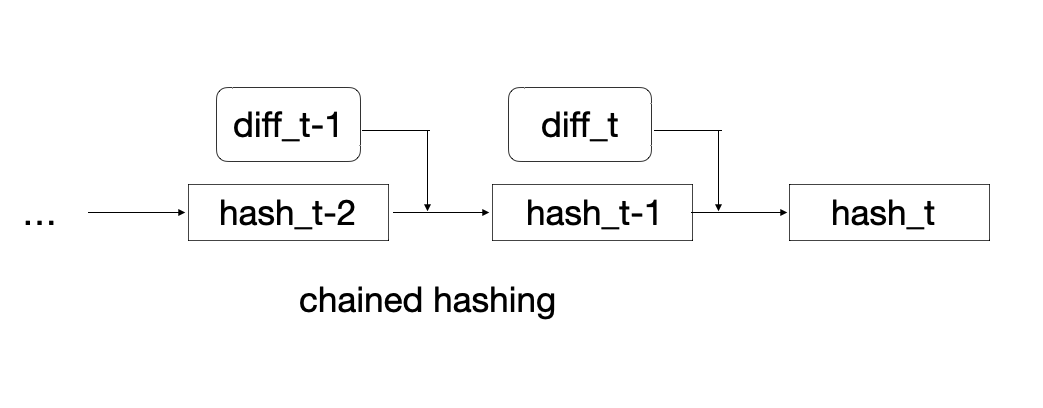

Note that on the left, transaction processing means repeated re-hashing of the whole ledger. To optimize, recursive or chained hashing is introduced3 (picture on the right). Now, nodes only hash the previous ledger hash and the new transaction content, as opposed to constantly re-hashing the whole ledger, which is better for efficiency4 and for reasons we’ll see below.

Another consequence of the chained hashing design is that history is now “hardened” in the sense that you can’t swap out a block with another block. If you were to change a block in the chained structure, you can do so, but you’ll end up modifying all the subsequent hashes as well.

Also: to avoid ambiguity in transaction processing, we can also imagine for now that previous ledger hash is included inside each transaction. Each node will run a heuristic to ensure they’re in sync with other nodes. Specifically, nodes occasionally exchange the last n hashes with neighbouring nodes and then fetch or contribute known transactions to establish the collective ledger.

5. The problem

Arguably, previous steps were expected engineering moves. The main problem is now in front of us. Recall that we have a P2P network that maintains a common chain of transactions. The ledger’s progression over time represented as a sequences of hashes.

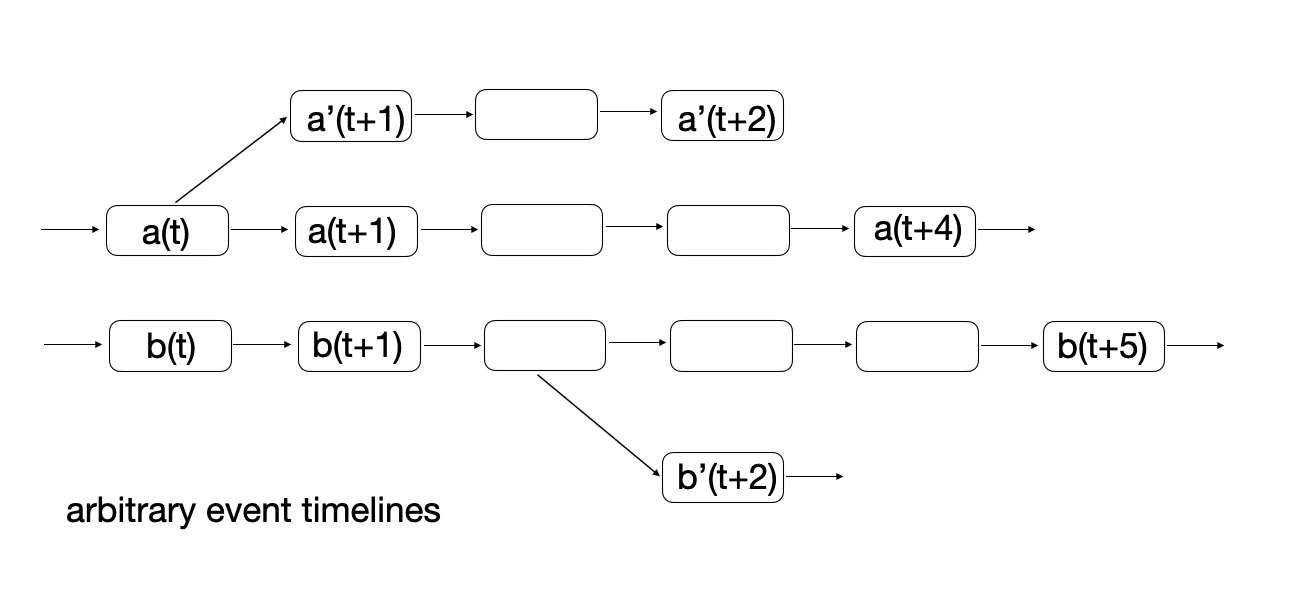

The problem is that an arbitrary number of possible competing histories can be created, as shown in the picture. If you’re a node in the network and a different history is presented to you, how do you decide if that’s your history, or not? Note that this essentially voting problem doesn’t have much to do with what we started with - physical gold’s behavior, yet it emerges here.

For example, such an alternative history may curiously lack a certain transaction, which was already billed out in the real world. Therefore, switching between histories is dangerous; it can mean loss of huge amounts of funds and renders the system completely useless. Another variant of this attack includes broadcasting a double spend transaction to intentionally split the network; half of the network believes in one history, the other half in another history. The network must be able to recover from such a split.

Observe that here the problem is not to decide which historical fork is the right one, as all forks are equally right. All of the transactions in all forks were signed by correct participants and therefore they’re all correct. A criterion for accepting a historical fork is needed, such that these two propreties are satisfied:

- Security: it’s not possible to double-spend.

- Flexibility: nodes can recover from network splits.

Let’s explore some ways how malicious history alteration could be mitigated.

6. How not to solve the problem

Attempts to defend against variants of the double-spend attack are below.

- Length-based cutoff: The longest chain is considered as the authoritative chain. In such a case, an attacker can artifically extend the chain to have the network swap back and forth between histories, resulting in a double-spend attack.

- Seal-based cutoff: The longest chain is authoritative, but a node will switch to a different chain only if the change doesn’t go deeper than

n(e.g. 50) hashes. Users will consider transactions finalized only if they’re buried underneath more thannhashes. With such a rigid rule, there’s danger of a permanent network split. At each point, an attacker can present a competing chain forking off the existing chain aboutnhashes away, resulting in one part of the network accepting the first chain and the other the second chain. Now a double-spend can be processed twice by two portions of the (split) network. - Rule-based cutoff: Attempt to introduce some rule (independent of the ongoing state) that’ll determine which fork is authoritiative. Say, we’ll choose the fork whose hashes are a minimal in terms of alphabetical ordering. The problem is - an attacker can simply mine for favorable hashes and overtake any fork and thus double-spend.

None of the attempted solutions works, and it’s unclear how to proceed.

7. “Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System”

Satoshi’s idea is to use the concept of “Proof of Work”, which was an esoteric concept back in 2008. More specifically, his idea is to use PoW to establish a secure voting criterion on what’s valid history. The criterion is such that it’s secure (history is sealed after a certain amount of events and thus prevents double-spend) and flexible (network forks get resolved and do not result in permanent splits). Satoshi introduces the following:

- Network nodes require a proof of work on each acceptance of new historical events

- Transactions are grouped into blocks and only blocks accompanied with a proof of work are accepted

- If there are multiple chain forks, the chain with the most cumulative work is considered authoritative

This makes forging an alternative history difficult. If I’m an attacker trying to swap out the current history with my own sequence of events, I’ll have to out-mine the network on over more than n blocks, before I get it to accept my chain. Thus, the security property is satisfied. As for chain splits (the flexibility property), if more than one competing chain exists, network nodes automatically choose the one with the most cumulative work. This makes any splits non-permanent, as the competition makes a single chain prevail.

Note that the difficulty of the PoW puzzle dynamically increases or decreases, based on the participation in the mining process.It’s shown in section 11 of the Bitcoin paper that an attacker attempting to compete with the main network’s fork drops exponentially.

Finally, recall that we started by simulating (physical) gold mining with solving proof of work puzzles: if you’re to create new gold, you mine. However, we’ve discovered that proof of work can be used for an entirely different purpose; and that is to seal a historical event line. We may then reuse the proof of work computation for two purposes:

- To secure the event line on the ledger and

- To emulate the process of gold mining

We ended up with the following: the (honest) collective has a stronger say than a resourceful attacker on a sort of anonymous voting problem, where what’s being voted on contains a specific structure. The structure here is the a cryptographically chained sequence and not an independent set of events, as it would be in the case of e.g. a series of independent referendums. The cryptographic structure of the chain makes outvoting the collective exponentially hard over the number of blocks, acheiving sealing of history. Another difference from independent referendum voting is that “voting” in Bitcoin is continually open; this is to achieve flexibility and prevent permanent network forks.

[1] Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system, PDF

[2] How to time-stamp a digital document: Haber and Stornetta, 1991, PDF

[3] Bit gold, Nick Szabo blog, 2005

-

Some years ago, a friend told me the following story. During the eighties and the personal computer boom, he dabbled in computers. His enthusiasm for computers and related topics fluctuated up and down. However, at some point in his teens, on a local journal’s frontpage, he saw a picture of a computer connected to a telephone. That triggered something in his adolescent mind, strated off curiousity on how to use modems and he never looked back. If there’s something general in the picture of a computer connected to a telephone which had the potential to trigger such a reaction in a young person’s mind, then the same matter is certainly present in the idea that a short blob of bytes in one’s personal computer can have monetary value. This is in fact a dream come true - bytes that extend into the real world, even though they exist exclusively inside a personal device. People will be attracted, only because of that and independently of any use-cases, stories of better future or the unfortunate abuse potential of this technology. ↩

-

Proof of work can be thought of “soft” or “flexible” cryptography. In “regular” cryptography, access is gated with an unattainable number of operations such as

2^128, in order to e.g. forge a cryptographic signature. Therefore, “regular” cryptography is a sort of “all or nothing” access cryptography, which idealizes what we have in the real world. In the real world, if someone really wants to rob your house, they could do so by paying a potentially high price and with lots of preparation. In the digital world, this could be modeled faithfully, by using a proof of work function instead of a “all or nothing” function. Access is gained with a substantial, but attainable number of operations, such as2^24to2^72. It turns out that, in some situations, solving the problem simply necessitates this “flexible” type of cryptography and not traditional “all or nothing” cryptography. We’ve already seen an example of that when we mentioned simulating mining of gold (together with the crazy idea of sending such solutions over chat apps or email). Anyone can mine gold and it’s attainable in practice. Proof of work is simply the right key for that keyhole. ↩ -

The same idea of hash chains was used in this 1991 paper by Haber and Stornetta: How to Time-Stamp a Digital Document. They tackled the question how to time-stamp documents in a trustless way. You could have a service that’ll time-stamp documents just by cryptographically signing them with a timestamp as they arrive from users. In collusion with submitters, such a signer can forge time-stamps single-handedly. The idea is to have the time-stamping service provide signatures over links of a hash chain, so that maliciously forward or back-dating documents would require breaking the chain. The chain is secured by trustworthiness of adjacent entities (humans, or organizations) in the chain, who aren’t expected to attest to something that didn’t happen. In that sense, the Haber and Stornetta chain was sealed by trustworthiness. ↩

-

This chained hashing scheme can be seen as a “unary tree” (as opposed to a binary tree) and a simplified variant of a Merkle tree, where the number of child nodes is set to one. Merkle trees and such concepts arise when we’re given a black box hash function, we hash a bunch of data and we ask questions such as: (1) What is the cost of proving that a subportion of the hashed data participates in the hash? (2) What is cost of updating the hash if we’re given some modifications to the underlying data? These questions were tackled by Ralph Merkle in 1979, but we’ll leave this topic for other explorations. ↩