How's it going in the world of boomerang cryptanalysis

I’m back-dating this blog post to chat about some surprising things I discovered in the area of boomerang cryptanalysis, a sub-area of symmetric key cryptanalysis. This was while I was working on finding a zero-sum for the full HAS-160 compression function, paper here, during my PhD. I loved everything on this project; the research and the coding - even though it’s not a very practical thing that’s being done here. Nonetheless, this pretty non-pratical research on zero-sums resulted in somewhat surprising practical findings; check below.

I also wanted to share the PoC source code (TBD, some minor clean up ongoing) that I used to derive the second order collision for HAS-160. It implements a boomerang differential trail search heuristic - I don’t think folks did this previously; for regular differential search trails, the best two papers/tools I worked with was this paper and the ARXTools open-source framework.

The implementation is akin to a constrained-down SAT solver that’s purposefully made less general, in order to be more efficient. As mentioned, this is PoC code, probably contains comments in my native (Serbian) language and is unusable without changes. If you’d like to read or understand any part of the code, please e-mail me and I’ll help to the best of my ongoing ability.

Let’s move on to the two surprising things I wanted to briefly chat about. Disclaimer: This blog post does not attempt to be self-contained, it assumes assumes familiarity with the topic; it’s a quick writeup rather than a comprehensive one.

1. Most boomerang attacks against ARX primitives 2000-2012 were flawed

Well, that’s the surprising thing. After wrapping up with this paper I realized that a SAT solver can be used to quickly all validate trails published in the litereature. Result: most of the boomerang attacks on ARX primitives from that period were based on contradictory trails.

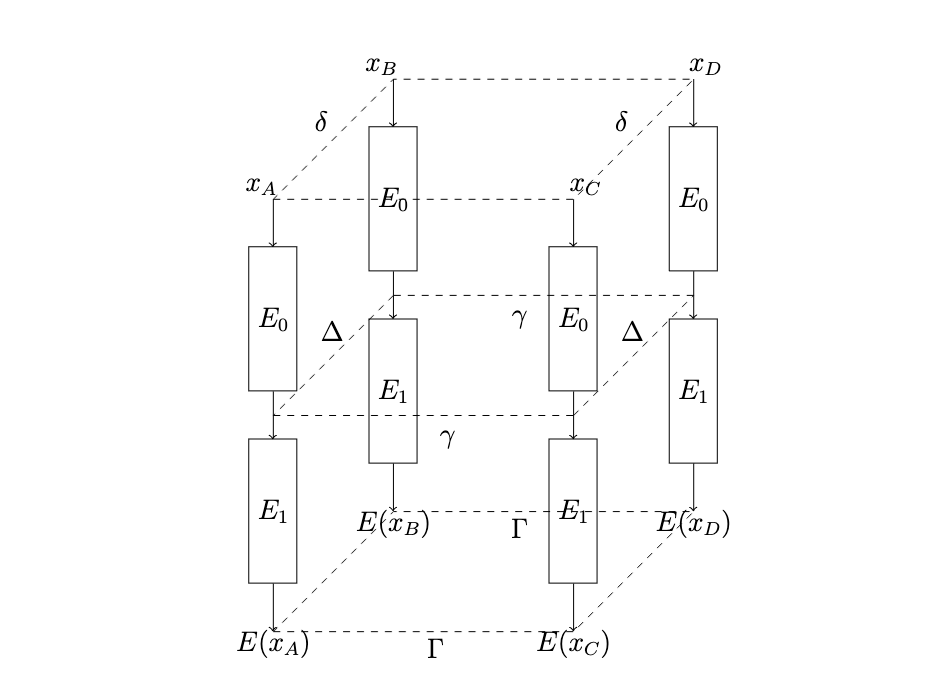

In a boomerang attack, we’re looking at a fixed differential trail on the front ( and the back side of the quartet and another differential trail on the left and right faces of the quartet. These trails must be compatible (and not contradictory). Papers from 2000-2012 would make best manual effort to ensure the trails do not overlap, however this is not sufficient for trails to be non-contradictory. There may be conditions that work together and propagate that are opaque to the trails themselves.

The fact that boomerang attacks can be wrong was first talked about here here and specifically shown for in the context of an attack on Blake. I wrote that up here and the main finding is that it was a rule rather than an isolated case. When crafting boomerang differential trails by hand, it’s very easy to make mistake; so easy that a mistake was made every single time.

There’s a parallel to be made with secure software development. Certain processes are just hard to get (implement) right, such as if you’re trying to write a parser for a complicated grammar in C. There’s almost certainly going to be memory issues.

Some developments that came later (2018 and 2020): probabilistic (in)dependence has been studied not only to validate an existing attack, but as an amplification factor, see this paper as well as this one. It seems that nowdays it’s expected that proposed trails are validated programmatically, which is a good thing.

2. “Unaligned” or “overlapping” boomerang trails

When folks talk about boomerang or rectangle differential trails, it’s all about differences in executions of quartets of primitives, as shown on the previous figure.

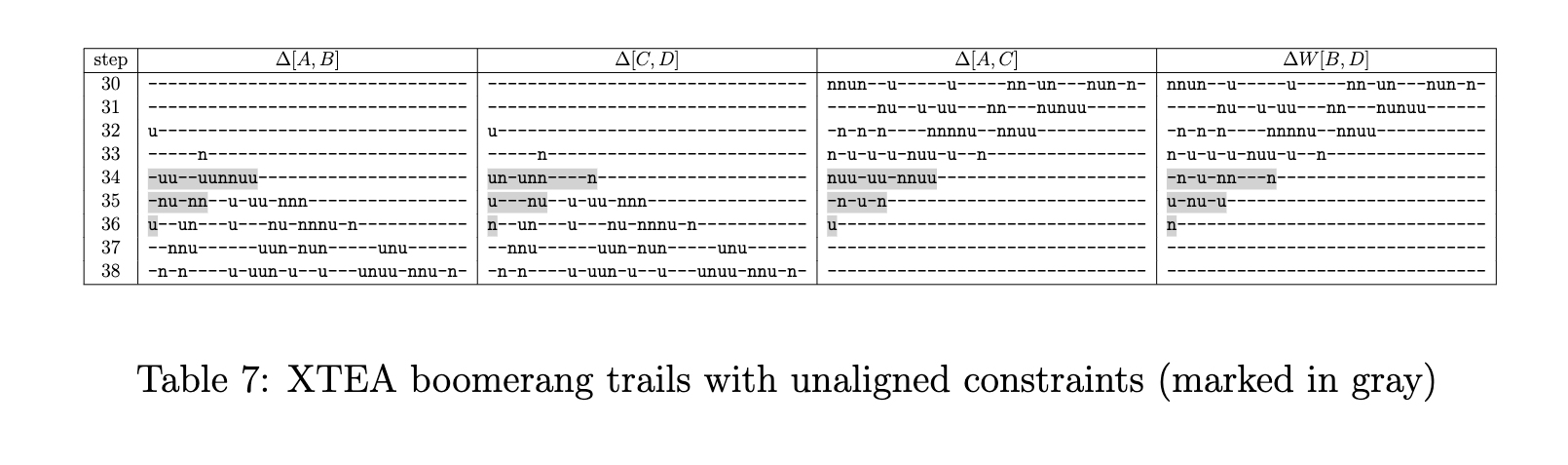

As per boomerang attack setting, differences between the opposite faces of the boomerang are assumed to be exactly equal. As such, we only talk about “pairs of differential trails”, not “quartets of differential trails”. There’s the question whether it’s possible to have a boomerang trail that has a four different trails, turns out the answer is yes - a SAT solver found one for XTEA without problems:

Once we’ve shown this is possible, the question is whether this type of “unaligned” trails can be useful in cryptanalysis. Intuition says that these trails will have lower probability than non-overlapping (regular) boomerang trails, however, I think it’d still be wortwhile playing with this and verifying how often such trails can occur in practice.

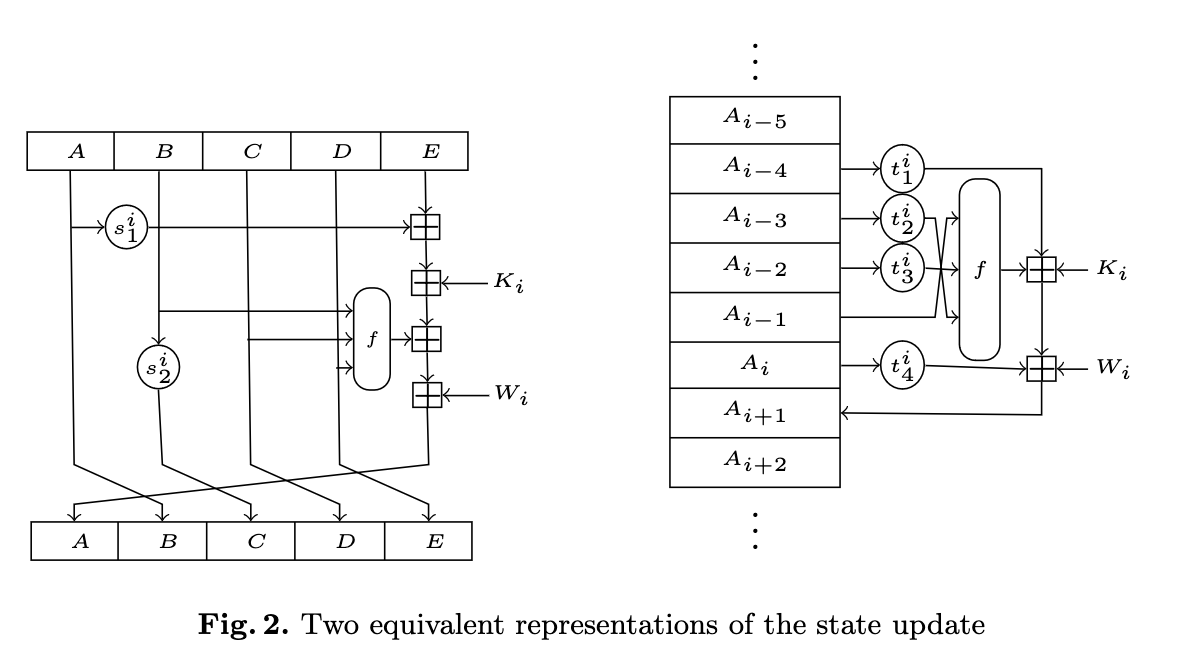

3. Visual representation matters

This is not at all a new discovery or anything close to that, but I feel it really is worth saying. There are two ways to think about a SHA-like hash function:

The one on the left contains redundancy, as the words are repeated in two consecutive rounds. The one on the right-hand side is more natural, it represents the function as a flow and does not contain any redundancy.

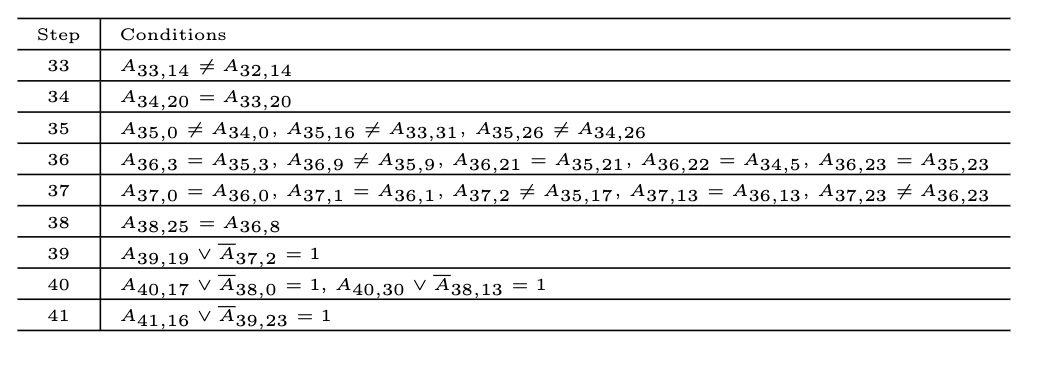

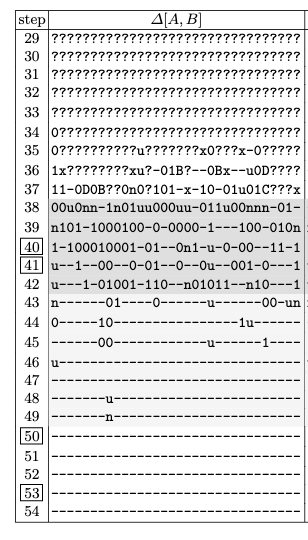

When it comes to differential trail representation, in the 2000-2012 papers with (contradictory) boomerang trails, a common way to represent differential trails was using tables, which look like this:

Compare this to this feedback-shift register representation of the trail (corresponding to the right-hand side of the picture):

You can see the hash function lists registers one after another, as the execution progresses. There’s no redundancy, it’s just much more natural and pleasant for the human eye.